Austria-Hungary Mobilizes Against Montenegro

By Erik Sass

The First World War was an unprecedented catastrophe that killed millions and set the continent of Europe on the path to further calamity two decades later. But it didn’t come out of nowhere. With the centennial of the outbreak of hostilities coming up in 2014, Erik Sass will be looking back at the lead-up to the war, when seemingly minor moments of friction accumulated until the situation was ready to explode. He'll be covering those events 100 years after they occurred. This is the 66th installment in the series.

April 29, 1913: Germany Promises to Respect Belgian Neutrality, Austria-Hungary Mobilizes Against Montenegro

The neutrality of Belgium, agreed by international treaty in 1839 following Belgium’s revolt against the Netherlands, was a cornerstone of peace and stability in Western Europe. With memories of Louis XIV and Napoleon always in the back of their minds, British diplomats insisted that Europe’s other Great Powers guarantee the neutrality of the new, independent kingdom in order to keep France contained. Ironically, the rationale for Belgian neutrality would shift in subsequent decades—but British commitment never wavered, as the little kingdom’s territorial integrity was still crucial to the European balance of power.

After Prussia’s stunning defeat of France and creation of the German Empire in 1870 and 1871, Belgian neutrality suddenly became a safeguard for France against Germany’s growing strength. Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, who had no desire to alienate Britain, reaffirmed Germany’s commitment to Belgian neutrality in 1871. Nevertheless, in the early years of the 20th century it was widely suspected that Germany might violate Belgian neutrality in an attempt to circumvent France’s new defensive fortifications and outflank French armies from the north. Of course this was exactly what the Germans envisioned in the Schlieffen Plan—and of course they had to deny it up and down.

British and French fears were shared by German anti-war socialists, who deeply distrusted Germany’s conservative military establishment (for good reason). Thus on April 29, 1913, a prominent Social Democrat, Hugo Haase, threw down the gauntlet in a speech to the Reichstag, noting, “In Belgium the approach of a Franco-German war is viewed with apprehension, because it is feared that Germany will not respect Belgian neutrality.” After this blunt reminder there was no way to avoid the subject, and the German government was forced to make a public declaration.

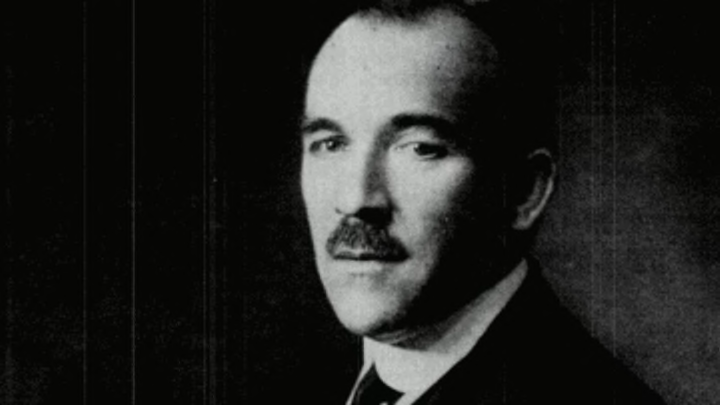

The government response was delivered by foreign minister Gottlieb von Jagow (above), who reassured the Reichstag that “Belgian neutrality is provided for by international conventions, and Germany is determined to respect those conventions.” The message was reiterated by war minister Josias von Heeringen, who promised parliament that “Germany will not lose sight of the fact that the neutrality of Belgium is guaranteed by international treaty.” Needless to say, both men were aware that the Schlieffen Plan called for the violation of Belgian neutrality—Jagow since January 1913 and von Heeringen since December 1912, at the latest. In fact, both were personally opposed to it on the grounds that it would provoke Britain to enter the war against Germany, as indeed it did (they were ultimately ignored, and in any event their private views can’t excuse these bald-faced lies to the public).

Austria-Hungary Mobilizes Against Montenegro

The fall of Scutari to Montenegro on April 23, 1913—the last major event of the First Balkan War—triggered yet another diplomatic crisis which threatened to provoke a much larger conflict. Spurred to action by the Austro-Hungarian war party led by chief of staff Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf, foreign minister Count Berchtold demanded that the Montenegrins withdraw from Scutari, which had been assigned to the new, independent state of Albania by the Great Powers at the Conference of London. Meanwhile, Berchtold also put pressure on the other Great Powers to back up their decision with the threat of force against Montenegro, currently under blockade by a multinational fleet—and if France, Britain, and Russia weren’t willing to use military action to enforce their will, he warned, Austria-Hungary would do it for them. But on April 2, Russian foreign minister Sergei Sazonov had insisted that Austria-Hungary could not act alone; Berchtold’s threat raised the possibility of another standoff between Austria-Hungary and Russia—or even war.

On April 25, 1913, the Conference of London refused Berchtold’s request for a naval bombardment of Montenegrin forces. Meanwhile, German foreign minister Jagow told the Austro-Hungarian ambassador in Berlin, Count Szogeny, that Germany would support military action by Austria-Hungary against Montenegro, even if it was unilateral (meaning, against the wishes of the other Great Powers); the next day the Germans warned the Conference that Austria-Hungary might proceed against Montenegro on its own. On April 28, Berchtold repeated his request for a naval bombardment, but (expecting another rebuff) also decided to go ahead with Austria-Hungary’s own military preparations.

On April 29, 1913, Austria-Hungary mobilized divisions in Bosnia-Herzegovina and began massing troops near the Montenegrin border. The following day, Jagow warned the French ambassador in Berlin, Jules Cambon, that if the situation spiraled out of control, resulting in a Russian attack on Austria-Hungary, Germany would stand beside her ally. On May 2, the Austro-Hungarian cabinet agreed to military measures against Montenegro, and the Germans repeated their support for aggressive action. Once again Europe teetered on the edge of disaster.

See the previous installment or all entries.