15 Fascinating Facts About Alfred Hitchcock

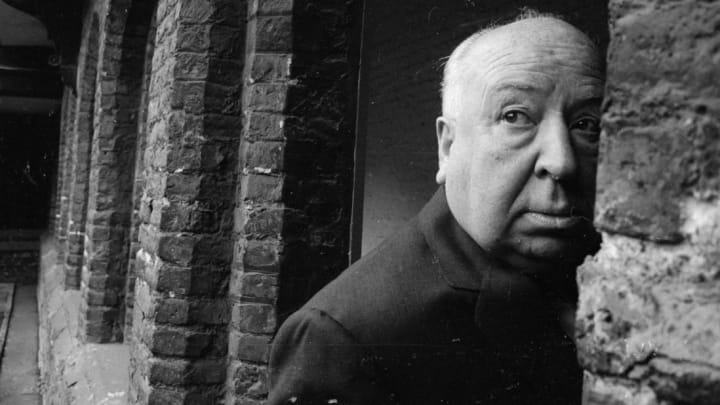

The shower scene in Psycho. The biplane chase in North by Northwest. The gas station attack in The Birds. They’re some of the most memorable and terrifying scenes in cinema history—and they came from the mind of one man: Alfred Hitchcock. The Master of Suspense, who went by the nickname “Hitch,” is also one of the most recognizable Hollywood icons, and his life was as fascinating as his films. Here are 15 things you might not have known about the legendary filmmaker, who was born in London on August 13, 1899.

1. Alfred Hitchcock was afraid of law enforcement ... and breakfast.

Hitchcock’s mastery of thrillers may have earned him the nickname the “Master of Suspense,” but the plucky filmmaker had phobias of his own.

His lifelong fear of police stemmed from an incident in his childhood when his strict father, William, punished him by sending him to the local Leytonstone police station on the outskirts of his family's home in east London. “I was just sent along with a note, I must have been four or five years of age, and the head of the police read it and then put me into the cell and said, ‘That’s what we do to naughty boys,’” Hitchcock later recalled of the experience.

Also, omelettes were decidedly not his favorite breakfast food. "I'm frightened of eggs, worse than frightened, they revolt me," he once said in an interview. "That white round thing without any holes … Have you ever seen anything more revolting than an egg yolk breaking and spilling its yellow liquid? Blood is jolly, red. But egg yolk is yellow, revolting. I've never tasted it."

2. Alfred Hitchcock began his work in silent films.

Known for the complex title sequences in his own films, Hitchcock began his career in cinema in the early 1920s, designing the art title cards featured in silent films. The gig was at an American company based in London called the Famous Players-Lasky Company (it would later become Paramount Pictures, which produced five Hitchcock-directed films). As Hitchcock later told French filmmaker François Truffaut in their infamous Hitchcock/Truffaut conversations, “It was while I was in this department, you see, that I got acquainted with the writers and was able to study the scripts. And, out of that, I learned the writing of scripts.” The experience also led Hitch to try his hand at actual filmmaking. “If an extra scene was wanted, I used to be sent out to shoot it,” he told Truffaut.

3. Alfred Hitchcock learned from another cinema master.

In 1924, Hitchcock and his wife Alma were sent to Germany by Gainsborough Pictures—the British production company where he was under contract—to work on two Anglo-German films called The Prude’s Fall and The Blackguard. While working in Neubabelsberg, Hitchcock was taken under the wing of expressionist filmmaker F.W. Murnau, who created the chilling Dracula adaptation Nosferatu, and was shooting a silent film called The Last Laugh. “From Murnau,” Hitchcock later said, “I learned how to tell a story without words.”

4. Most of Alfred Hitchcock's early films are lost, but a 1923 silent melodrama was discovered in New Zealand.

Only nine of Hitchcock’s earliest silent films still exist. The earliest surviving film he worked on, a 1923 melodrama titled The White Shadow—about twin sisters, one good, one evil—was thought lost until three of the film’s six reels were found sitting unmarked in the New Zealand Film Archive in 2011. The film reels were originally donated to the Archive in 1989 by the grandson of a Kiwi projectionist and collector.

While the film was technically directed by leading 1920s filmmaker Graham Cutts, the 24-year-old Hitchcock served as the film’s screenwriter, assistant director, and art director.

5. Alfred Hitchcock brought sound to British movies.

The 1929 movie Blackmail, about a murder investigation headed up by the murderer’s fiance, was Hitchcock’s first hit film, and also the first “talkie” film released in Britain. (The first full-length talkie, The Jazz Singer, was released in the U.S. in 1927.)

While Blackmail was originally conceived and created as a silent film, the final cut was dubbed with synchronized sound added in post-production using then-state of the art audio equipment imported from the U.S.

6. Alfred Hitchcock popped up on screen all the time.

The most constant image in Hitchcock’s films seem to be Hitchcock himself. The filmmaker perfected the art of the cameo, making blink-and-you’ll-miss-them appearances in 39 of his own films.

His trickier appearances include the single-location film Lifeboat, where he appears in a weight-loss advertisement in a newspaper read by one of the film’s characters. The only film he actually speaks in is 1956’s The Wrong Man; his traditional cameo is replaced by a silhouetted narration in the introduction. That replaced a scrapped cameo of the director exiting a cab in the opening of the film.

7. Alfred Hitchcock was as successful in front of the camera on the small screen as he was behind the camera on the big screen.

By 1965, Hitchcock was a household name. That was the same year his long-running anthology TV series, Alfred Hitchcock Presents—which began in 1955 and was later renamed The Alfred Hitchcock Hour after episode lengths were stretched from 25- to 50-minute runtimes—came to an end.

The series was known for its title sequence featuring a caricature of Hitchcock's distinctive profile, which was replaced by Hitchcock himself in silhouette. But Hitchcock also appeared after the title sequence to introduce each new story. At least two versions of the opening were shot for every episode: An American opening specifically poked fun at the show’s network advertisers, while Hitchcock usually used the European opening to poke fun at American audiences in general.

7. Alfred Hitchcock literally wrote the encyclopedia entry on how to make movies.

The filmmaker would write (at least part of) the book on the medium that made him famous.

Hitchcock personally contributed to writing a portion of the “Motion Pictures, Film Production” entry in the 14th edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica, giving typically cheeky first-hand insight into the fundamentals and technical aspects of filmmaking.

On the practice of moving the camera during a shot, Hitchcock wrote, “it is wrong to suppose, as is all too commonly the case, that the screen of the motion picture lies in the fact that the camera can roam abroad, can go out of the room, for example, to show a taxi arriving. This is not necessarily an advantage and it can so easily be merely dull.”

8. Alfred Hitchcock popularized the MacGuffin.

Even if you don’t know it by name, you know what it is. The MacGuffin is the so-called motivating element that drives a movie’s plot forward. Think: the eponymous statue in The Maltese Falcon, or the briefcase in Pulp Fiction, or the airplane engine plans in Hitch’s own The 39 Steps.

The term was coined by Angus MacPhail (note the prefix in his surname), Hitchcock’s screenwriting collaborator on films like Spellbound and The Man Who Knew Too Much. Even though such plot details were supposed to be important, Hitchcock didn’t seem to think they truly mattered. “The main thing I've learned over the years is that the MacGuffin is nothing. I'm convinced of this, but I find it very difficult to prove it to others,” Hitchcock told Truffaut in 1962, highlighting how the audience never finds out why the government secrets (a.k.a. the MacGuffin) in North by Northwest truly matter. “Here, you see,” Hitchcock said, “the MacGuffin has been boiled down to its purest expression: nothing at all!”

9. Alfred Hitchcock scrapped his own documentary about the Holocaust.

Hitch’s films flirted with mentioning the escalating tensions in Europe that would spark World War II, like in the shocking plane crash climax of 1940’s Foreign Correspondent. But the film Hitchcock collaborated on about the explicit horrors of the war would go unseen for decades.

Memory of the Camps, a 1945 documentary filmed by crews who accompanied the Allied armies that liberated those in the Nazi death camps at the end of the war, was stored in a vault in the Imperial War Museum in London until 1985. Originally commissioned by the British Ministry of Information and the American Office of War Information, Hitchcock served as a “treatment advisor” at the behest of his friend Sidney Bernstein, who is the credited director of the film. But the final film was scrapped because it was deemed counterproductive to German postwar reconstruction.

The film was put eventually together as an episode of PBS’s FRONTLINE, and aired on May 7, 1985 to mark the 40th anniversary of the liberation of the camps.

10. Alfred Hitchcock didn't want you to see five of his famous films for decades.

Vertigo may have topped many best-of movie polls, but for over 20 years, between 1961 and 1983, it and four other Hitchcock classics were almost virtually impossible to see. It turns out it was Hitchcock’s fault that Vertigo, Rear Window, Rope, The Trouble with Harry, and The Man Who Knew Too Much were purposefully unavailable to the general public.

The filmmaker personally secured full ownership to the rights of the five films per a contingency clause in the multi-film deal he made with Paramount Pictures in 1953. Eight years after the release of each film, the rights reverted back to Hitchcock, which, in the years before Blu-ray and DVD, seemed like a financially savvy move on Paramount’s part. Three years after Hitch’s death in 1980, Universal Pictures acquired the film rights to all five classics, making them available once again.

11. Alfred Hitchcock didn't want to work with Jimmy Stewart after Vertigo.

Everyman actor Jimmy Stewart worked with Hitchcock a number of times, including as the nosy, wheelchair-bound photographer in Rear Window, and as the dastardly murderer in the “one-take” film Rope. After Stewart appeared in Vertigo in 1958, the actor prepared to appear in Hitchcock’s follow-up a year later, North by Northwest. But Hitch had other plans.

The director felt that one of the main reasons Vertigo wasn’t more of a smash hit was because of its aging star, and vowed to never use Stewart in any film ever again. Hitch wanted actor Cary Grant instead, and, according to author Marc Eliot’s book, Jimmy Stewart: A Biography, “Hitchcock, as was his nature, did not tell Jimmy there was no way he was going to get North by Northwest.” But when Stewart grew tired of waiting, and took a part in the movie Bell Book and Candle instead, “Hitchcock used that as his excuse, allowing him to diplomatically avoid confronting Jimmy and maintaining their personal friendship, which both valued.”

12. Alfred Hitchcock personally funded Pyscho.

When Hitchcock approached Paramount Pictures—where he was under contract—to put up the money to make Psycho, the studio balked at the salacious story. So Hitchcock financed the movie himself, foregoing his normal salary in exchange for 60 percent ownership of the rights to the film; Paramount agreed to distribute the film. To cut costs even more, the filmmaker enlisted his relatively cheaper Alfred Hitchcock Presents TV crew and shot the film on less pricey black and white film. Hitch’s gamble worked: He reportedly personally earned $6 million from Psycho—about $50 million in today's dollars.

13. Alfred Hitchcock wouldn't allow theaters to let anyone—not even the Queen of England—in to see Psycho once it had started.

Psycho (1960) has one of the best twists in movie history—and Hitchcock went to great lengths to not only make sure audiences didn’t spoil that twist, but to make sure they enjoyed the entire movie before the twist.

Hitchcock attempted to buy all copies of author Robert Bloch’s source novel to keep the twist under wraps in cities where the movie opened. The promotional rollout of the film was controlled by Hitchcock himself, and he barred stars Janet Leigh and Anthony Perkins from doing interviews about the movie. He also demanded that theaters in New York, Chicago, Boston, and Philadelphia adhere to strict theatrical showtimes and not allow admittance after the movie had started.

Marketing materials for Psycho included lobby cards meant to be prominently displayed with the message, “We won't allow you to cheat yourself. You must see PSYCHO from the very beginning. Therefore, do not expect to be admitted into the theatre after the start of each performance of the picture. We say no one—and we mean no one—not even the manager's brother, the President of the United States, or the Queen of England (God bless her)!”

14. Alfred Hitchcock loved movies that were not "Hitchcockian."

The filmmaker had a habit of screening films in his studio lot office every Wednesday, and his daughter Patricia revealed that one of his favorite films—and, in fact, the last movie he personally screened before his death—was the 1977 Burt Reynolds movie Smokey and the Bandit.

15. Alfred Hitchcock never won a competitive Oscar.

Hitchcock is in the bittersweet class of venerable filmmakers like Stanley Kubrick, Orson Welles, Charlie Chaplin, Ingmar Bergman, and more who never received their industry’s highest honor as Best Director. Hitchcock did get Oscar nominations for directing Rebecca (which took home Best Picture), Lifeboat, Spellbound, Rear Window, and Psycho. But he personally went home empty-handed every time.

When the Academy finally honored him with the Irving G. Thalberg Memorial Award in 1967, his long-time-coming speech was only five words long: “Thank you, very much indeed.”

This story has been updated for 2020.