6 Forgotten Nursery Rhymes and Their Meanings

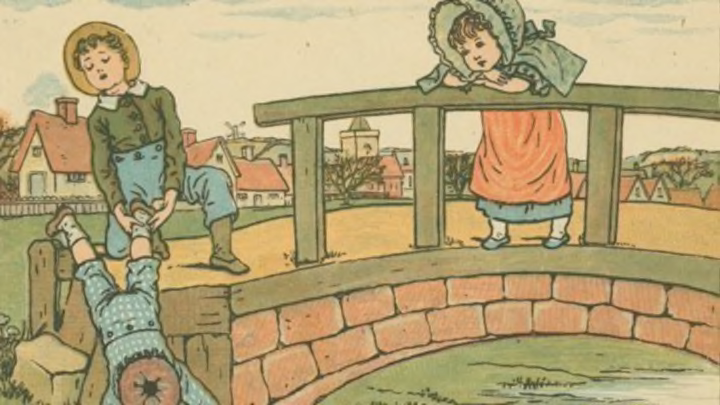

Recently, I found a beautiful 19th century children’s book called Mother Goose or the Old Nursery Rhymes. In it, illustrator Kate Greenaway had drawn the demure expressions and swan-like curvatures that had made her famous in her day, all in rare color. Many of the rhymes were familiar—Little Boy Blue and Little Miss Muffett—but some of the more baffling rhymes were new to me. Nursery rhymes often (but not always) contain more layers than first appear. Sometimes they were intrinsic parts of games, history, or political opinion. Here are some of the more unfamiliar rhymes and what, if anything, lies behind their meaning.

1. "Elsie Marley has grown so fine"

Elsie Marley has grown so fine, She won’t get up to serve the swine; But lies in bed till eight or nine, And surely she does take her time.

Old British pubs were a fertile ground to birth rhymes and song, especially if that song was about the lady who ran the pub. Elsie Marley was a real lady who ran a pub called The White Swan. She was much lauded, “her buxom presence and lively humour being the means of attracting customers of all ranks of society.” The swine in question were undoubtedly her clientele. These lines were only a tiny bit of a popular song, likely outliving their source because you can so easily fit in a lesson about arrogance and laziness for children.

While Marley might have started as an 18th century pub song, it was later appropriated by the Scottish to describe the battle for the crown between Scottish Charles Stuart and King James II. The Scottish version turns Elsie to “Eppie” and has her losing all her money following the Stuart cause.

2. "Cross Patch, lift the latch"

Cross Patch, lift the latch, Sit by the fire and spin; Take a cup, and drink it up, Then call your neighbours in.

If you were to hear this nursery rhyme being chanted around the 18th century kindergarten monkeybars, it would probably be a taunt. A “crosspatch” was a person who was cranky, or cross. The “patch” meant fool or gossip, apparently because fools in centuries past were identifiable by their haphazard clothing repairs. In this little story, Miss Selfish locks her door, drinks all the good stuff up by herself, and then lets her neighbors come in.

In a slight variation, Cross Patch is compared to “Pleasant Face, dressed in lace, let the visitor in!” In that version nobody wants to play with ole Crosspatch, because she’s a pill. So she has to sit and make yarn all by herself all day. Whereas Pleasant Face is throwing a party.

More Articles About Nursery Rhymes:

manual

3. "Tell Tale Tit"

Tell Tale Tit, Your tongue shall be slit; And all the dogs in the town Shall have a little bit.

Here is another great example of the school yard taunt. Pinning down just what was meant with “tell tale tit” is the only complicated part of this rhyme. Our modern definition of “tit” has been in use for a very long time, though not nearly as sexualized. In a copy of Webster’s Dictionary from 1828 it is described in lovely, florid language as “the pap of a woman; the nipple. It consists of an elastic erectile substance, embracing the lactiferous ducts, which terminate on its surface, and thus serves to convey milk to the young of animals.” The same entry, strangely enough, identifies a tit as a tiny horse. Soon it evolved to mean anything small: tittering, titmouse, tit-bits (predecessor to tid-bits). A tell tale tit is a crybaby tattletale. It was a popular insult, having many variations just in English school yards alone. And we all know what happens to tattletales; it involves sharp knives and hungry dogs. Not a rhyme that succeeded into the sanitized gentility of the 20th century.

4. "Goosey, goosey, gander, where shall I wander?"

Goosey, goosey, gander, where shall I wander? Up stairs, down stairs, and in my lady's chamber. There I met an old man who would not say his prayers,Take him by the left leg, throw him down the stairs.

Sometimes nursery rhymes make absolutely no sense—unless there’s a hidden meaning to them. Of course, children seldom look for that meaning. Even by 1889, “goosey gander” was children’s slang for blockhead, but the phrase had to come from somewhere. Some people think it refers to a husband’s “gander month”—the last month of his wife’s pregnancy, where, in centuries past, she’d go into “confinement,” and not leave her home for fear of shocking the populace by her grotesque condition, so her husband was free to wander all the ladies' chambers he wanted. But most historians think this nursery rhyme is about “priest holes.” That was a place where a well-to-do family would hide their priest and thus their Catholic faith during the many times and places in history Catholicism was prosecutable, particularly during the reign of Henry VIII and the upheaval of Oliver Cromwell. “Left-footer” was slang for Catholic, and any person caught praying to the “Catholic” God was praying wrong. Throwing them down the stairs would be the least those mackerel-snappers would have to worry about.

5. "My mother, and your mother"

My mother, and your mother, Went over the way; Said my mother, to your mother, "It's chop-a-nose day."

Sometimes, even rhymes that seem about to burst from the lurid story that spawned them turn out to be nothing more than a catchy rhyme. “Chop a nose day,” I suspected at first, had something to do with grotesque medieval social justice—but if it is, it has been lost to time. The Chop-a-Nose rhyme was more a medieval version of “Head and Shoulders, Knees and Toes.” Mothers and paid nurses would use it as part of a game to teach toddlers body parts, culminating in a pretend “chop” of the child’s nose.

6. "All around the green gravel"

All around the green gravel The grass grows so green And all the pretty maids are fit to be seen; Wash them in milk, Dress them in silk, And the first to go down shall be married!

The more you research nursery rhymes of previous centuries, the more you realize people used to really love forming circles together and singing. They were called “ring games,” and involved holding hands, walking in a circle, and chanting, usually culminating in everyone falling down. The most long-standing example was, of course, Ring Around the Rosie (which, by the way, almost certainly had nothing to do with Bubonic plague), but the Green Gravel circle game is even more interesting because nearly every geographic area of the UK had their own slightly different version of it. In this version, the first girl to plop down on her bottom (or more demurely, into a crouch) at the last line is either out, and turns her back to the circle (though still holding hands) or gets to kiss a boy standing in the center of the circle. In some versions he even gets to call out her name to end the game, increasing the chances that she just might be the first to marry.