10 Things Revealed About the Nixon White House

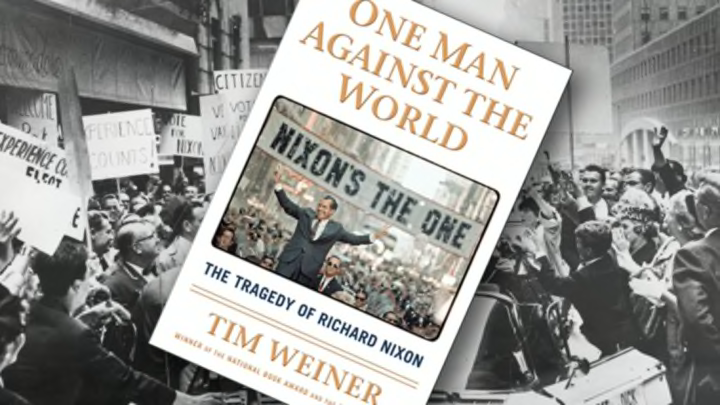

Tim Weiner, author of One Man Against the World, writes of Richard Nixon, “He wielded power like a Shakespearian king.” Nixon’s story is well known—the tragedy of a “great, bad man” who, while fighting wars and subversives, would begin spying on—and lying to—friend and foe alike. Weiner, a Pulitzer Prize winner, is a master researcher, delving into source documents to reconstruct histories with nuance and insight.

The Nixon White House delivered an unprecedented trove of material. Practically everything was recorded, and accounts from all of the key players would eventually be delivered through grand jury testimony, diaries, and minutes from White House committees. “The result,” he writes, “is that every quotation and each citation herein is on the record: no blind quotes, no unnamed sources, and no hearsay statements.”

The book is an extraordinary look at how the personal, political, and historical meld together and influence the way power is wielded at the highest echelon. Here are ten things One Man Against the World reveals about Richard Nixon and the presidency.

1. Nixon thought Kennedy stole the 1960 election.

Nixon narrowly lost the 1960 election to John F. Kennedy, and believed “to his dying day” that the presidency had been stolen from him. Fourteen thousand votes in three states would have made the difference. He returned to California where he proceeded to lose the 1962 gubernatorial election by three times as many people as had voted against him for the presidency. When he conceded defeat for the governorship, drunk, he famously told the gathered press, "You won’t have Nixon to kick around anymore.”

But he wasn’t finished. He spent the next four years “ceaselessly cultivating future campaign supporters: corporate kingpins and foreign rulers, county chairmen and congressional leaders. He was blazing a trail back to power.” He raised $30 million from American donors—then a record amount—and made secret (and Weiner argues, illegal) political overtures to the South Vietnamese government (the war being the dominant political issue of the day). He was set for a comeback, and won the presidency in 1968.

2. He sent a secret message to China in his inaugural address.

Getty Images

The saying “Only Nixon could go to China” refers to Nixon’s career as a strident anti-communist and Cold Warrior. His overtures were seen as coming from a position of strength, and the visit was a long time in the making. During his inaugural address, he directly addressed the Soviet Union, saying, “Our lines of communication will be open.” The next line was a coded message to the Chinese government: “We seek an open world—open to ideas, open to the exchange of goods and people—a world in which no people, great or small, will live in angry isolation.”

The phrase “angry isolation” referred to an essay on China that he had written for Foreign Affairs, a celebrated journal devoted to foreign policy. In that article, he wrote, “There is no place on this planet for a billion of its potentially able people to live in angry isolation.” The Chinese government picked up on Nixon’s message, and took the unprecedented step of printing the entirety of his inaugural address in the People’s Daily, official newspaper of the Chinese Communist Party. Nixon visited China in 1972.

3. Even the National Security Agency thought Nixon’s wiretaps were “disreputable.”

During his time in office, Nixon wiretapped friend and foe alike. He trusted no one and hated leaks most of all. One aide who was wiretapped later wrote, “You cannot square a personal friendship and total trust and intimacy with his authorizing of tapping your phone...you cannot run a government that way.” By 1973, 1,600 people were on the U.S. government’s watch list, including anti-war activists, politicians, and journalists. The National Security Agency’s official history calls the government surveillance “disreputable if not outright illegal.”

4. He hated domestic politics and wasted little effort on it.

Getty Images

Nixon hated domestic politics, which he regarded as “building outhouses in Peoria.” He ordered the assembly of a “Domestic Council,” which would be the local counterpart to the National Security Council. He was eventually told that such a program was impossible because he had never bothered to define an actual domestic agenda. The so-called “war on crime” was useful in that it helped him score political points and expanded wiretapping statutes. He signed the Environmental Protection Agency into law despite believing it to be a capitulation to those interested in “destroying the system.” Domestic politics simply didn’t matter enough to warrant a fight. “This country could run itself domestically without a president,” he said. “You need a president for foreign policy.”

5. He was a proponent of the “madman theory.”

In 1969, he wanted the secretary of defense to “exercise the DEFCON,” referring to America’s state of military readiness. (DEFCON 5 means things are fine; DEFCON 1 means imminent total thermonuclear war.) DEFCON isn’t an arbitrary shorthand for politicians and the public. Changing its status means shifting military disposition, from moving warships to having pilots ready to leap into their bombers and erase countries from the map. Nixon wanted the DEFCON changed to convince Moscow that he was insane and thus not to be trifled with. This was called the “madman theory.”

6. He practiced for the end of the world.

Getty Images

Not long after taking office, the president participated in a dress rehearsal for World War III. He was flown aboard the Airborne Command Post, a nuclear command and control aircraft. (Four Airborne Command Posts remain operational today; no single plane can run the apocalypse effectively.) From there, he was walked through what might be expected if nuclear war broke out, and how to order the deployment of intercontinental ballistic missiles, and so on. His chief of staff took notes during the rehearsal, writing at the time that the president had “a lot of questions about our nuclear capability and kill results. Obviously worried about the lightly tossed-about millions of deaths.”

7. He was against executive privilege before he was for it.

Once the Watergate scandal broke, Nixon fought madly to protect members of the White House staff from having to testify before Congress. To shut things down, he decided to invoke “executive privilege,” which allows members of the executive branch to resist subpoenas and interference from the legislative and judicial branches. Twenty-five years earlier, Truman used that power to keep Congress—eager to find communists—from poring through White House personnel records. One congressman who, at the time, fought bitterly against executive privilege? Richard Nixon. (In fact, the first chapter of his 1962 memoir is devoted to his opposition to it.)

8. He kept the White House tapes because they were worth millions of dollars.

The biggest question one might ask about Richard Nixon concerns his famous tapes. Why did he record everything and, more importantly, why didn’t he destroy the tapes once it was clear that they might convict him? Concerning the first, Weiner asserts that Nixon recorded everything as a hedge against Henry Kissinger, his national security advisor and eventual Secretary of State. He knew Kissinger would eventually write a book about working in the White House, and he knew that Kissinger would lionize himself. Nixon believed the tapes would be valuable not only in writing his own memoirs (in which he looks better than Kissinger), but also as a unique resource in and of themselves.

In short, the tapes would be worth millions of dollars. As such, he held onto them until the bitter end. Nixon was no fool, though. Once the sharks started circling, he knew the tapes needed to be destroyed, but there was a problem: who would strike the match? It’s not like the president of the United States could load up a wheelbarrow, cart them to the south lawn of the White House, and start a bonfire. By this time everyone learned of the tapes (New York Post headline at the time: NIXON BUGGED HIMSELF). In fact, nobody could risk destroying them without almost certainly going to prison. And so the tapes remained, and continue to surprise all of us even to this day.

9. Nixon vowed there would be “no whitewash at the White House.”

Getty Images

Not long after Dwight Eisenhower chose him as a running mate in 1952, Nixon was accused of having a political slush fund. Bill Rogers, Eisenhower’s eventual attorney general, investigated and found no wrongdoing. He encouraged Nixon to go on television and defend himself. Nixon followed that advice, and gave what became known as the “Checkers speech,” in which he admits to having only one time in his life taken a campaign gift. Someone on the trail heard that Nixon’s daughters wanted a puppy, and one day a crate containing a dog arrived at the Nixon residence. His daughters were thrilled, and named the dog Checkers. “And I just want to say this right now,” vowed Nixon, “regardless of what they say about it, we’re going to keep it.”

Rogers would later spend four unhappy years as Nixon’s secretary of state. When the president finally discussed Watergate in a national address from the Oval Office, it was again Rogers who encouraged him. In that speech, Nixon famously said, "There can be no whitewash at the White House." Those guilty, said Nixon, must "bear the liability and pay the penalty." (He wasn’t talking about himself at the time, but it still worked out that way.)

10. He resigned in 1974, but the business of state went on.

Nixon resigned on August 8, 1974, after it became clear that the House would impeach him for obstruction of justice in the Watergate investigation, and that the Senate would probably convict. The next day, the White House staff and service staff gathered, and Nixon said goodbye to them in a brief speech. He then walked to Marine One and departed. David Ransom, a foreign service officer, observed from the White House balcony the moment of liftoff. He described it as “almost a haunted scene.” Two men stood with Ransom: the White House chef and the secretary of defense, James Schlesinger. Said Schlesinger, as he emptied his pipe: “It’s an interesting constitutional question, but I think I’m still the secretary of defense. So I am going back to my office.” Schlesinger asked the chef what he was going to do now. “I’m going to prepare lunch for the president,” he said, and went off to prepare a midday meal for Gerald Ford.