17 Clues About Puzzlemaster Will Shortz

By the mag

As told to Jen Doll.

America's foremost crossword guru on how to get a clue.

1. When I was growing up, every once in a while, our family would start a jigsaw puzzle in the evening.

Everyone would drift off to bed, but I was a night owl. I stayed up. I cannot leave a puzzle unfinished. I would just keep going, and finish it at five in the morning. When everyone got up in the morning, too bad—the puzzle was done.

2. In eighth grade, I wrote a paper on what I wanted to do with my life: I wanted to be a professional puzzle maker.

I imagined I would live in a garret somewhere cranking out my little puzzles for $10 apiece, and I imagined a life of poverty, and that was OK, because that was what I really wanted to do.

3. There’s a book called Language on Vacation, which came out in 1965. I wrote [the author] for advice.

He wrote back a very thoughtful three-page, single-spaced letter explaining all the reasons why I should not have a career in puzzles and why it was basically impossible.

4. I’m the only person in the world who’s ever majored in puzzles. (Shortz majored in enigmatology at Indiana University.)

Two years ago a guy majored in magic, and he looked upon me sort of as a mentor.

5. The summer before I started law school, I interned for PennyPress puzzle magazines.

The spring of my first year in law school, I wrote my parents that I’d be dropping out at the end of the year to work in puzzles. You can imagine how well that went over. My mom wrote back a very thoughtful letter saying, “This is a terrible idea,” and listing all the reasons why. At the end she said, “We love you no matter what you decide.” I thought her reasoning was good, so I did get my law degree. Then I went into puzzles.

6. When I first started at The New York Times in 1993, I took over for Eugene Maleska, who was 36 years older than me.

Shortly after that, a man wrote me, saying that solving crosswords edited by me was like taking a new mistress—not unpleasant, it just took getting used to. That’s how personal crosswords are.

7. I think of myself as more than a crossword person.

I’m interested in all kinds of puzzles. I wrote books of Sudoku. I helped introduce KenKen—a number logic puzzle invented in Japan—to the United States. I invent literally hundreds of varieties of puzzles. I do new sorts of things every Sunday on NPR, but the Times is the most prestigious job in puzzles. It’s just a great position. It’s creative. I’m stretching my mind every day. I have a laugh every day.

8. Every day is different.

Looking at mail. Editing clues. Making puzzles for NPR. Planning the American Crossword Puzzle Tournament. Planning the World Puzzle Championship.

9. I’ve also opened a table tennis center.

It’s one of the largest in North America. I play table tennis every day. June 30 was my thousandth consecutive day of table tennis. That helps keep me sane.

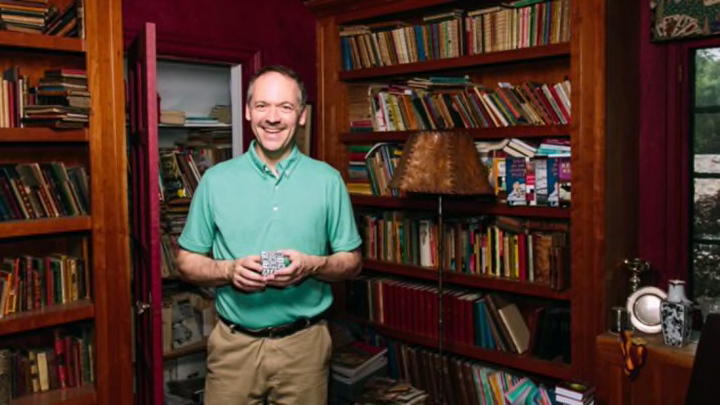

Photo by Andrew Hetherington

10. I get 75 to 100 crossword submissions a week.

Every puzzle has to be looked at and responded to: yes or no. My current assistant, Joel, really does the bulk of the mail work now, looking at submissions for puzzles he thinks have possibilities. He and I decide which will be yesses, and everyone gets a reply, and usually some comments on the puzzle.

11. On average, about half the clues in the puzzles are mine.

The most important thing is accuracy. Anything I’m not 100 percent sure of I verify, and then I edit for the proper level of difficulty, freshness, color, and just a sense of fun.

12. After the puzzles are edited we type-set them and send them to four test solvers, and they all call with comments and corrections.

Then the puzzles are sent to the Times electronically, where a friend of mine—a former national crossword champion—goes in, prepares the files, and tests the puzzles again. Every puzzle is test-solved and checked multiple times.

13. I get people who think there are errors all the time.

They are very rare. There are more than 32,000 clues, and there were five errors in all last year. People love to catch me in errors.

14. I do mind errors.

I really mind errors.

15. Election Day, 1996: Still my favorite crossword of all time.

It broke expectations. It goes against logic to have a puzzle with two solutions. That had never been done before. This was the year that Bill Clinton and Bob Dole ran for president. The clue for the middle answer was “headline in tomorrow’s newspaper,” and the answer could be “Clinton Elected” or “Bob Dole Elected.” Either one worked with the crossings. For example, the first down clue crossing the theme answer was “black Halloween animal.” You could have made that cat, forming the c of Clinton, or bat, forming the first b of Bob Dole. The next one was “French 101 word,” and you could do lui or oui, and each of these succeeding answers worked the same way. The clue did double duty.

16. Why do we like puzzles? I think it’s a way of putting the world in order.

Every day we’re faced with problems. Most of them do not have clear-cut solutions, and we just muddle through. We do the best we can, but we never know if we’ve got the best solution. The great thing about a human-made puzzle is we can take the challenge through from start to finish. And when we’re done, we know we have achieved perfection. We don’t get that feeling much in everyday life.

17. I’ll never get tired of doing this.

I genuinely enjoy everything I do, and I love the people I come in contact with through puzzles. They’re well-rounded people. They know lots of things. They’re a nice group to hang out with. Someone once said, “If you ever tire of becoming a writer, that means you have become tired of life,” and I feel the same way about puzzles. If you ever get tired of puzzles, then you’re tired of life.