15 Archaeological Sites Revealed By Climate Change

In 1991, two tourists in the Italian Alps discovered Ötzi, a well-preserved, 5300-year-old mummy that was exposed by a melting glacier. It was a sensational find that has provided important information about the customs, diet, tool use, and migration of ancient peoples. As the planet warms, melting permafrost, sea ice, and glaciers are revealing more and more ancient mummies and other treasures that help archaeologists fill in the gaps of human history, bit by bit.

But as quickly as new discoveries are made, they are made vulnerable. Today, archaeologists around the world are racing against rising tides, melting ice, erosion, and other symptoms of climate change to document and protect significant sites and artifacts before they disappear.

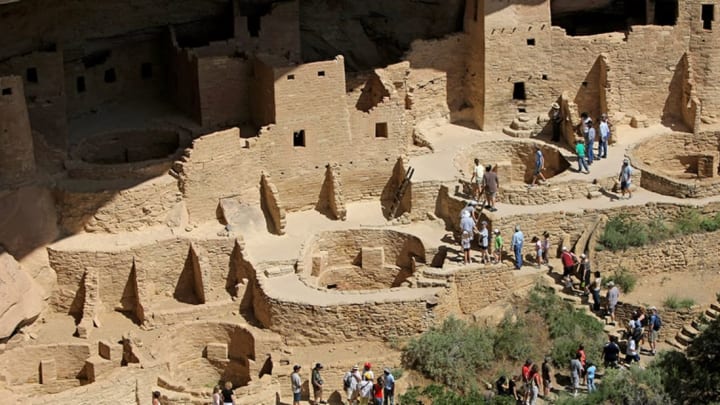

1. ANCESTRAL PUEBLOANS // MESA VERDE NATIONAL PARK

Two years ago, the Union of Concerned Scientists released a report highlighting Mesa Verde National Park in southwestern Colorado as one of 30 U.S. sites most vulnerable to climate change. The ancient Puebloans first constructed dwellings on top of the mesa around 1400 years ago, then moved down into canyons to build sophisticated multistory apartment buildings made of wood beams and sandstone.

There are almost 5000 archaeological sites here, but fast-rising temperatures over the past half a century, in combination with declining precipitation, have contributed to more frequent and intense wildfires. That, in turn, has destroyed petroglyphs and exposed new sites and artifacts, which then become vulnerable to the erosion and flooding that are common after fire.

2. ALTAI MOUNTAINS BURIAL MOUNDS // SIBERIA AND OTHER LOCATIONS

On the edge of Siberia, extending across the borders of China, Kazakhstan, Mongolia, and Russia, the Altai Mountains hold ancient tombs of nomadic horsemen and horsewomen known as the Scythians. (You might know the Scythian horsewomen by their more colloquial name: Amazons.) The tombs are a veritable time capsule of life on the Eurasian Steppe some 2500 years ago. They contain sacrificed horses and mummified human remains, including the famous 5th century BCE Ukok Princess, otherwise known as the Siberian Ice Maiden. Researchers have also found everyday household items that are rarely so well-preserved, including furniture, wooden objects, textiles, and saddles.

Researchers suggest that there may have been an important trade route here long before the Silk Road that connected East and West, raising exciting possibilities about the transmission of cultural knowledge and customs more broadly in Asia and the Middle East. But time may be running out to solve the many mysteries that remain about the Scythians and subsequent groups that populated the region. The permafrost that has kept these tombs intact for millennia is melting, creating great urgency for archaeologists to document as many sites as possible and preserve the remarkable artifacts as fast as they can.

3. SAN NICOLAS ISLAND // CALIFORNIA

Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

Embedded in sea cliffs of the Santa Barbara Channel Islands are fragments of human history going back 11,000 years. As the ocean advances, archaeologists are racing to save the artifacts that tell important stories of Native Californians here. Those who have read Scott O’Dell’s Island of the Blue Dolphins know the story of one famous Native Californian, a young woman who lived alone on San Nicolas Island for 18 years before she was discovered by an expedition, taken to the mainland, and baptized Juana Maria. (Sadly, she died just seven weeks after arriving on the mainland.)

In 2009, archaeologists made a remarkable discovery on San Nicolas Island while walking along an eroded sea cliff: two redwood boxes containing a fascinating array of artifacts. The site was a snapshot of human interaction and change on the island in the first half of the 19th century. European glass and metal, Nicoleño tribal artifacts, and bone harpoons indicated that the boxes had been used after Russian and Native Alaskan sea otter hunting parties visited the island. Archaeologists say it’s possible that Juana Maria herself could have placed the boxes there.

There are untold treasures like these up and down the California coast and Channel Islands. But as recent video of Northern California homes teetering on the edge of an eroded sea cliff reveals, the coastline can change quickly and dramatically. Many important archaeological sites may be lost to the sea before they are ever discovered.

4. CHAN CHAN // PERU

Six hundred years ago, the city of Chan Chan on the coast of Peru was the seat of the vast Chimú empire that extended hundreds of miles from central Peru almost to the Ecuadorian border. It was the largest pre-Columbian city in South America, and features adobe palaces, temples, and labyrinthine passageways.

That this city was able to flourish in a coastal desert is evidence of the sophistication and ingenuity of its engineers and urban planners. Despite the lack of rainfall here, the city had extensive agriculture and lush gardens, thanks to complex irrigation systems that included wells and water diversion systems.

But strong El Niño episodes are expected to become more frequent in the coming years, contributing to a rapid erosion of the ancient city. With predictions of increasingly extreme rainy and dry periods, the future of this city that flourished for centuries before being conquered by the Incas remains uncertain.

5. ISLAND OF MEROE // SUDAN

Wikimedia Commons // CC BY-SA 2.0

While not a real island, the Island of Meroe is a complex comprising Meroe, the longtime capital of the ancient Kingdom of Kush, and the religious sites of Naqa and Musawwarat es Sufra. Located near the Nile Valley, it was built more than 2000 years ago in what was then a grassland.

Its most magnificent feature is the Temple of the Lion God, Apedemak, dedicated to the Meroites fertility deity and decorated with elaborate carvings and hieroglyphics. As the climate has become drier, however, grasslands have given way to wind-blown Sahara sands, and the painted reliefs and carvings of this exquisite site are eroding away.

6. THULE CULTURE // GREENLAND

The Thule people emerged in Alaska around 2000 years ago and steadily expanded their range until entering Greenland around 1000 years ago. These tough folk survived their harsh environment by building pit houses deep into the ground using whale bone, stone, and walrus skin. Now, the sea is claiming these remains.

The culture survived and adapted to at least two prior periods of climate change before disappearing during the 14th and 15th centuries. Today, warming threatens what remains of this once-resilient Arctic culture. As Greenland’s buffering sea ice and permafrost melt, Thule and other human settlements going back thousands of years are yielding to massive storm surges and thawing earth. Archaeologists have noted a staggering rate of coastal change and artifact loss in the past decade alone, and the situation is bound to worsen as thawing accelerates.

7. WALAKPA BAY // ALASKA

The grassy coast south of Barrow on Alaska’s Northern Slope has been inhabited by semi-nomadic Native Alaskans for 4000 years but is fast giving way to an eroding coastline and thawing permafrost.

Twenty years ago, rapidly eroding coastal bluffs began exposing human remains—and evidence that the site contained artifacts far older than previously thought. Since then, sea level rise, fierce coastal storms, and thawing are taking more and more of Walakpa and its irreplaceable artifacts year by year.

Almost as quickly as they’re being uncovered, they are melting into the earth and sea, preventing archaeologists from collecting valuable information about ancient whaling cultures and the natural history of the region. It’s now one of fastest disappearing coastal sites in the world.

8. CHINCHORRO MUMMIES // CHILE

The Chinchorro were a prehistoric fishing culture that lived in villages along the coast of northern Chile and Peru in the Atacama desert. For about 3500 years, mummification was an important feature of their culture. Everyone, regardless of social class, gender or age, got mummified—even fetuses. They removed brains and organs and stuffed the bodies with straw, reeds, grass, ash, and animal blood to preserve their shape. Before burial they painted the bodies, which remained well-preserved for millennia in the arid desert climate.

But about a decade ago, some of the Chinchorro mummies housed at the University of Tarapacá started to excrete a black ooze. The world’s oldest known manmade mummy collection, some of which had survived in good condition for 7000 years, was disintegrating. What could have caused this?

Eventually, scientists attributed the breakdown, at least in part, to rising humidity inside the museum, which caused an increase in a common microorganism that feeds on the collagen of mummified skin. It wasn’t just happening in the museum, though—humidity is on the rise in the entire region, raising serious concerns about the effects on hundreds of mummies still in their original burial sites. Archaeologists hope that a new climate-controlled museum, scheduled to open in 2020, will prevent further deterioration. But by then, it may be too late for some of the mummies.

9. HISTORIC JAMESTOWN // VIRGINIA

The English who settled Jamestown chose the site in 1606 for its strategic location on the tidal James River. It was then surrounded by water on three sides and well inland from the coast, which made it easier to defend against the Spanish. But the first permanent English colony in what is now the United States is today threatened by the very characteristics that made it desirable to the settlers. The waters here have been rising at a rate twice the global average, and Jamestown is now just 5 feet above water.

Jamestown is a fascinating window onto early American life. In addition to military facilities, there are burial sites, churches, homes, and a blacksmith shop, and a glassblowing factory that represents one of the earliest examples of industry in North America.

Almost a million artifacts were damaged by a single storm event, Hurricane Isabel, in 2003. Some projections suggest waters could rise another two feet here by 2050, and 6 feet by the end of the century.

10. CASTLES AND SHIPWRECKS // IRELAND

The coast of Ireland has taken a beating from powerful winter storms during the past few years. Storms have revealed submerged treasures—ancient drowned forests and Spanish Armada shipwrecks—but also caused castles and stone forts to crumble. On Connemara’s tidal Omey Island, a fierce 2014 storm uncovered Neolithic dwellings and medieval burial sites, while a protective wall around the historic Bunowen Castle was undermined by waves near the town of Ballyconneely.

Reports of damage up and down the Irish coast tell of similar discoveries and destruction. Researchers say coastal midden sites—organic trash deposits that tell archaeologists much about everyday life of ancient peoples—are particularly vulnerable. Last year, the Technology Institute of Sligo hosted a conference called Weather Beaten Archaeology to engage researchers, policymakers, and the public in finding compromised sites and working together to protect them.

11. CHINGUETTI // MAURITANIA

Wikimedia Commons // CC BY-SA 3.0

As the Sahara moves south, desertification threatens a Mauritanian heritage site and medieval trading center that once attracted thousands of caravans as well as Sunni pilgrims en route to Mecca. Sand is rapidly infiltrating the city of Chinguetti, an oasis that flourished between the 13th and 17th centuries.

Both desertification and increasingly destructive flash floods during rainy seasons create powerful sandstorms that blow through the city. Under threat are a 13th-century stone mosque and an important collection of Islamic manuscripts vulnerable to the dry, hot air and sand.

12. TURTLE MOUND // FLORIDA

The Timucuan people of central and northeastern Florida were skilled hunters, fishermen, and farmers. After European contact, however, their population declined, and disease outbreaks, particularly smallpox, took a devastating toll. Eventually the tribe died out; survivors likely joined the Spanish or neighboring tribes like the Seminole.

But over the course of 1000 years, the Timucuan living near what is now the city of New Smyrna created large midden mounds of oyster shells, discarded bones, pottery shards, and other trash items. Turtle Mound is the largest, and on an otherwise flat coastal landscape, the 35-foot hill stands out. Coastal erosion now threatens the site, but a joint effort by the National Park Service, scientists, and the public to protect Turtle Mound has led to the creation of a “living shoreline” comprised of restored mangroves, marsh grass and oyster shells. This has slowed erosion, though the site remains at risk from future sea level rise and storms.

13. ORKNEY ISLANDS // SCOTLAND

On the windblown Orkney Islands off the north coast of Scotland, culture after culture—including Gaels, Scots, and Vikings—left a physical record of their presence. And while coastal erosion is an ever-present threat to Scottish archaeology, violent storms coupled with sea level rise have recently been ripping away chunks of coast at an alarming rate.

One famous Orkney site at risk is Skara Brae, a Neolithic farming village believed to be between 4000 and 5000 years old. Because most of the structures and furnishings in dwellings here were made from stone rather than wood, they're well-preserved compared to other sites of a similar age. Built into a sand dune, the village has been protected by a sea wall for the past century. But ever-strengthening storms and storm surges may soon prove too much for it.

At the same time, storms are revealing new Orkney sites. On the island of Sanday, one storm exposed what turned out to be a Bronze Age burnt mound on the beach that archaeologists estimate to be more than 3500 years old. The mound contained a room where stones were heated before being pushed into a water trough. Archaeologists aren’t sure what function this served, but speculate that it could have been a kitchen, sauna, or even a boat-building facility. The challenge now is to protect the site before a major storm destroys it. Archaeologists are recruiting locals to regularly monitor Sanday sites like this and report their condition using an app that lets them upload photographs and messages to a monitoring center.

14. ABORIGINAL ROCK ART // AUSTRALIA

Across Australia, Aboriginal rock art sites have fallen victim to vandals, feral animals, and development. But fire has done its share of damage, too, and is likely to become a larger threat in the future. That’s because Australia is becoming hotter and dryer, making bush fires burn more intensely.

An increase in frequency and intensity of wildfires is already exposing rock art sites to heat and soot. And in some cases, measures to prevent wildfires have had unintended consequences: In the northwest Kimberley region, prescribed government burns to prevent larger, more destructive fires have destroyed some sites believed by some to be among the oldest in the world.

15. UNDERWATER ARCHAEOLOGY AROUND THE WORLD

Climate change is creating opportunities and barriers for underwater archaeologists. As the Arctic melts, researchers are able to pinpoint shipwrecks that had previously been sealed beneath thick ice. Archaeologists from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration recently discovered two 19th-century whaling ships believed to be part of a 33-ship whaling fleet that sunk off the coast of Alaska in 1871 after getting trapped in thick ice. With ice now thinning and disappearing altogether, NOAA researchers were able to use remote sensing equipment to locate two of the ships.

But climate change isn’t all good news for underwater archaeology. As storms and sea level rise create more erosion, coastal sediments could bury shipwrecks and other underwater artifacts. Ocean warming could also force the migration of invasive species, including Lyrodus pedicellatus, a type of shipworm that is a major threat to wooden structures in the North Atlantic. Ocean acidification may pose an additional threat: Metal corrosion on iron and steel ship structures could be hastened by more acidic water.

All photos courtesy of Getty Images unless otherwise noted.