The Murky Origins and Controversial History Behind the Song “Cotton Eye Joe”

If you were going to make a movie set in 1995, there would be a few surefire ways to instantly evoke the era in question. A character might pick up a newspaper with Bill Clinton on the front page—or they could open a mailbox and find a 3.5-inch promo floppy disk from AOL. Better yet, they could switch on the radio and sing along to one of the year’s most unforgettable earworms, “Cotton Eye Joe.”

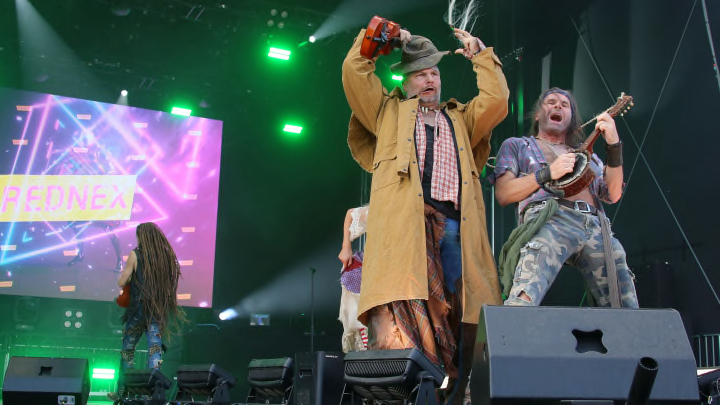

For those who don’t remember this bizarre moment in history, “Cotton Eye Joe” was a massive novelty hit for Rednex—a Swedish techno group founded by producers Janne Ericsson, Örjan Öberg, and Pat Reiniz (also known as Patrick Edenberg). The trio enlisted five performers to dress up in straw hats and dirty overalls—signifiers of poor rural America—and be the faces of the group. The quintet claimed in their official bio to be from Brunkeflo, Idaho.

Where Did You Come From?

Released in 1994, the fiddle-fueled “Cotton Eye Joe” was actually a reworking of an old American folk song, and thanks to its undeniable catchiness, it do-si-doed all the way to No. 25 on the Billboard Hot 100 in 1995.

“Cotton Eye Joe” remains a staple of weddings and sporting events, and in 2016, filmmakers Daniel Scheinert and Daniel Kwan selected the Rednex tune as the theme song for their 2016 film Swiss Army Man, starring Daniel Radcliffe. (Scheinert came up with the idea by asking, “Hey, what if the whole movie was just scored by the worst song?”) While it’s doubtful anyone remembers all the lyrics, one line from the song is forever burned into everyone’s brains: “Where did you come from, Cotton Eye Joe?”

With respect to the history of the song itself (often titled “Cotton-Eyed Joe”), “Where did you come from?” is a fascinating question. As with many American folk tunes, the author and origins are unknown, yet there’s a lot historians do know about this enduring ditty.

Murky Origins

The first known published version of “Cotton Eye Joe” appeared in Alabama writer Louise Clarke Pyrnelle’s Diddie, Dumps, and Tot, or Plantation Child-Life, a 1882 children’s book about the antebellum South. Pyrnelle drew heavily on her own childhood experiences on her father’s cotton plantation, and the novel gives credence to what most experts now hold as fact: “Cotton-Eyed Joe” originated with enslaved people well before the Civil War. Pyrnelle’s version describes the character of the title as an ugly man (“His eyes wuz crossed, an’ his nose wuz flat / An’ his teef wuz out, but wat uv dat?”) who swoops into town and steals the narrator’s sweetheart.

While the book was initially praised for its use of Black dialect, those accolades have since been reconsidered. The Encyclopedia of Alabama notes that the book’s “caricatures of Southern Blacks, its derogatory language, and its uncritical romanticization of slavery” are often seen as “distasteful to modern audiences” and that today’s readers “can see from Pyrnelle’s descriptions of [Black people] that, while praising the bonds between Black and white individuals, she shared the common prejudices of the day.”

“Ef it hadn’t ben fur Cotton-eyed Joe,” the jilted narrator sings, “I’d er ben married long ergo.” That basic plot line—boy loses girl to mysterious charmer—drives most iterations of “Cotton-Eyed Joe,” including the one Texas-born “song catcher” Dorothy Scarborough included in her 1925 book On the Trail of Negro Folk Songs. As Scarborough writes, she learned parts of the tune from “an old man in Louisiana,” who picked it up from enslaved people on a plantation.

Three years earlier, in 1922, the noted Black cultural historian and longtime Fisk University chemistry professor Thomas W. Talley shared a slightly different rendition in his book Negro Folk Rhymes. The son of formerly enslaved people from Mississippi, Talley came across a version wherein “Cotton-Eyed Joe” isn’t just a person, but also a dance: “I’d a been dead some seben years ago / If I hadn’t a danced dat Cotton Eyed Joe.” The song ends by saying Joe has “been sol’ down to Guinea Gall,” which again implies he was enslaved.

Lover’s Lament

Regardless of where, exactly, the song was born, it spread quickly throughout the South, becoming a square dance staple. An 1875 issue of The Saturday Evening Post contains a story referencing the song, and in 1884, The Firemen’s Magazine dubbed the tune “an old, familiar air.” The first 78 rpm recordings of “Cotton-Eyed Joe” began surfacing in 1927, when the string band Dykes Magic City Trio cut the earliest known version.

While the trio’s lively take contains the standard lover’s lament—“I’d a been married 40 years ago if it hadn’t been for old Cotton-Eyed Joe”—it also borrows lines from “Old Dan Tucker,” another folk classic with pre-Civil War roots.

Ol’ Joe is nothing if not an adaptable character. Among the stories collected in Talley’s posthumous 1993 book, The Negro Traditions, is “Cotton-Eyed Joe, or the Origin of the Weeping Willow.” Here, Joe is a fiddler whose instrument was made from his dead son’s coffin. Generally, Joe is a villain, but legendary soul-jazz songstress Nina Simone doesn’t sound mad at the guy in her 1959 live version. Simone sings her gorgeous ballad from the perspective of a woman who loved Joe long ago and is now ready to marry another man. “I come for to show you my diamond ring,” she sings—maybe out of spite, though her plaintive delivery suggests she still has feelings for the troublemaker.

Where Can You Go?

One of the biggest mysteries of the song is what is meant by cotton-eyed. As per the Random House Historical Dictionary of American Slang, the term describes “prominent whites of the eyes.” Others believe old Joe was wasted on moonshine, blind from drinking wood alcohol, or suffering from a medical condition like trachoma, cataracts, glaucoma, or even syphilis. (Urban legend holds that “Cotton-Eyed Joe” is really about STDs in general, though there’s little evidence to support this theory.)

It is estimated that have been more than 130 recorded versions of the song since 1950. This includes a 1992 collaboration by American country great Ricky Skaggs and the Irish group The Chieftains that inspired Rednex’s version. There’s also a haunting version by indie rockers Manchester Orchestra on the Swiss Army Man soundtrack.

It’s safe to say none of the versions are as cloying or (arguably) culturally insensitive as the Rednex recording. In a 2021 interview with Songfacts, founding producer Pat Reiniz admitted that the group “knew very little about the American hillbilly/redneck culture” when they released “Cotton Eye Joe.” Having since done some homework, Reiniz says the group will continue to function as a “50/50 tribute/parody of that lifestyle.”

Given its roots in American slavery, “Cotton Eye Joe” has been deemed racist by some cultural critics, and in 2021, a Canadian hockey team stopped using the song for that very reason. These types of conversations have become increasingly common in the world of American folk music, a democratic art form in which songs are handed down from generation to generation. Because lyrics and meanings are always changing, Rednex doesn’t get to have the final word. Where “Cotton-Eyed Joe” goes now is completely up to the next person who feels like singing it.

A version of this story ran in 2016; it has been updated for 2022.