The Dubious Legend of Virgil's Pet Fly

By Lucas Reilly

Here at Mental Floss, we come across a lot of "facts" that, upon further examination, don’t hold up. Like, did Benjamin Franklin invent the concept of Daylight Saving Time? Not really. (Several ancient cultures seasonally adjusted their clocks, and Franklin only jokingly pondered having people wake up earlier. The modern version was proposed in 1895 by George Hudson, an entomologist who wanted extra daylight so he could collect more insects.) Do sea cucumbers eat through their anuses? Some, but not all. (One species, P. californicus, uses its backdoor as a second mouth.)

Other facts have been trickier to debunk because the historical record was being snarky or sarcastic: Was Amerigo Vespucci, for whom America is likely named, a measly pickle merchant? (Ralph Waldo Emerson said so, but he was probably being snide.) Did people in 16th century France wipe their butts with geese? (A quotation from François Rabelais's comic series of novels Gargantua and Pantagruel has been confused as evidence, but Rabelais was a bawdy satirist.)

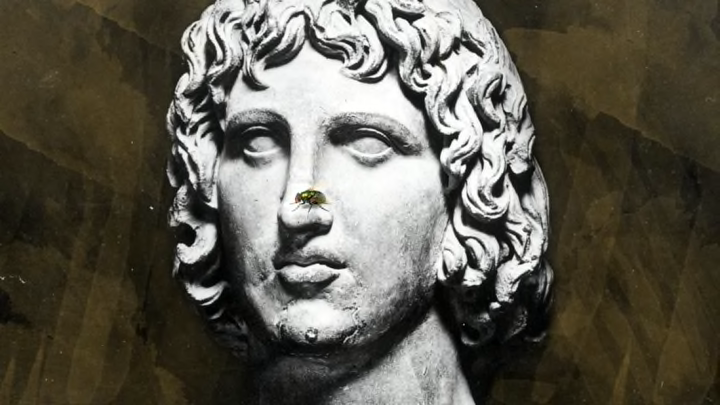

Yet one of our favorite dubious fun facts—a Trojan Horse that has snuck into a handful of trivia books—concerns Virgil, the Roman poet and author of the Aeneid. The story goes that Virgil had a pet housefly, and when the insect died, Virgil spent 800,000 sesterces—nearly all of his net worth—for an extravagant funeral. Celebrities swarmed the poet’s home. Professional mourners wailed. An orchestra performed a lament. Virgil drafted verses to celebrate the fly’s memory. After the service, the bug’s body was ceremoniously deposited in a mausoleum the poet had built on his estate.

Virgil wasn’t losing it: It was all a scheme to keep the government’s fingers off his land. At the time (and this part is true), Rome was seizing private property and awarding it to war veterans. According to legend, Virgil knew the government couldn’t touch his property if his estate contained a tomb, so he quickly built a mausoleum, found an arthropod occupant, and rescued his house.

It’s a great story! It’s also unsubstantiated. None of Virgil’s contemporaries mention the poet throwing a lavish funeral—especially one for a housefly. The story probably has roots in an old poem that’s been (incorrectly) attributed to the poet called "The Culex." In the poem, a fly (or, depending on your translation, a spider or gnat) wakes up a man just as a snake is lurking nearby. The man kills both the insect and serpent, but soon regrets killing his winged protector. He builds the bug a marble headstone with this epitaph:

O Tiny gnat, the keeper of the flocks Doth pay to thee, deserving such a thing The duty of a ceremonial tomb In payment for the gift of life to him.

Most scholars don’t believe that Virgil wrote "The Culex." But as Sara P. Muskat, a research assistant at the University of Pittsburgh during the 1930s, wrote in a short essay, Virgil was regularly the subject of this kind of mythmaking. Shortly after his death, people in his hometown of Naples alleged he was the founder of the city. (He wasn’t.) Others claimed he had been the city’s governor. (He hadn’t.) By the Middle Ages, Virgil was depicted as a magician or dark wizard who could communicate with the dead. (He couldn't.)

“There is then no evidence, ancient or medieval, that I can find to support the story that Vergil had a pet fly and gave it an elaborate funeral,” Muskat writes. “It seems quite inconsistent with Vergil’s usual behavior, and may indicate that the period of myth-making about Vergil has not yet closed.”

Like our friendly imaginary fly, perhaps it’s time for this factoid to bite the dust, too.